Was Jesus black?

1 of the (several) highly contentious problems in the Church of England at the moment is the question of racism, its extent in the Church, and appropriate and effective responses to it. Information technology has long been a question of involvement to me, since soon after coming to faith I felt that God might be calling me to inner-city, multicultural ministry building—a call which has not worked out in the fashion I expected, but which nevertheless has shaped various decisions over the years. Working in industry prior to ordination, I chose to live in the multi-ethnic town from which the manufactory drew its workers, and during ordination preparation, I chose placements in multicultural inner urban contexts. I currently live in a multi-ethnic (and multi-generational) household of nine, and pb a multi-ethnic group in our church.

I have previously written virtually the theological imperative of indigenous diverseness amongst the people of God, and the evidence for the way that worked out in the primitive church building. But I am not convinced that the Church building of England is tackling this in a helpful way, and it is in danger of assuasive ideological arroyo to ignore the historical reality. So when I heard of the twenty-four hours conference on changing our thinking well-nigh race in the Church building, organised by the Archbishops' Committee for Minority Ethnic Anglican Concerns (CMEAC), in collaboration with the British & Irish Association for Applied Theology (BIAPT), I felt I needed to attend.

My first and overall impression of the conference was (ironically) the lack of diversity. Although the master speakers were ethnically diverse and coming from different places around the world (one big advantage of doing things on Zoom rather than in person), there seemed to me to be a distinct lack of theological and philosophical diversity: all came from a radical/liberation/womanist position, and there were no real disagreements betwixt their perspectives. 1 of the discussion sessions did involve evangelical and orthodox voices, exploring the role of UKME people in church planting and mission. Merely there was a notable absence of voices from conservative black-led churches, such as the major Pentecostal perspectives, or from orthodox and evangelical churches who are engaging finer with questions of race.

This illustrates ane of the major mistake-lines in the discussion within the Church of England at the moment. A friend of mine who was a member of CMEAC some years agone said that this reflected her own experience; every bit an orthodox/evangelical on the committee, she felt every bit though she was a lone vox. If those who are near concerned near seeing questions of race addressed in the Church are speaking in a different annals of linguistic communication, with different theological assumptions, and a unlike philosophical arroyo to the issue compared with the majority of the Church, then we are bound to find the conversation frustrating.

Stephen Cottrell, Archbishop of York and a long-standing member of CMEAC, gave a good and engaging opening comment, highlighting the kinds of things I have explored in my previous manufactures, and landing on Rev vii.nine as a fundamental text.

The first main speaker was Anthony Reddie, who is Director of the Oxford Centre for Faith and Culture at Regent'due south Park College, University of Oxford, and is a well-known every bit a speaker and widely published in this area. I don't think I can summarise his presentation (and the papers are not being made available; I asked) merely there were several things from his paper and his answers to questions that stood out.

Offset, he immediately commented 'Black Liberation Theology has nothing to do with Marxism or Disquisitional Race Theory'. I can encounter why he wanted to say this up front, in order to anticipate and address common criticisms that accept arisen in response to the prominence of Black Theology in the debates nearly race. Merely information technology was notable that Reddie used the phrases 'Blackness Theology' and 'Black Liberation Theology' interchangeably, and he has previously been quite clear that 'Black Theology' does not refer to the theology done by black Christians—indeed, that yous do non have to be a Christian to engage in Black Theology, and that most people in black-led churches would not espouse Black Theology. Liberation theology, in its origins in Latin America, was strongly shaped by Marxist assumptions and interpretations of guild, in two main ways. The start was to meet order in binary terms as conspicuously divided between the 'oppressors' and the 'oppressed', and the second was to understand this in primarily textile terms. These both felt like potent themes in Reddie's presentation.

It should be noted that, whilst something of a 'trigger' term in popular discourse, Marxism as an intellectual position is not that uncommon in the academy. I recollect my own PhD supervisor, Christopher Rowland, would be happy to be described as having a Marxist outlook, and this led him to both a practical and academic interest in marginal and liberation movements in the history of Christianity. But this outlook tends towards seeing the world in terms of power dynamics, rather than any other kind of meaning. Chris ended up despairing of any possibility of anyone knowing what a text like the Volume of Revelation might actual mean, in any objective sense, and so his interest shifted rapidly to the diverse dissimilar ways the text had been used in history, without any particular regard to whether such uses continued well with the text itself.

Critical Race Theory was similarly built-in out of a frustration that apparently objective discourse (in scientific discipline, economics, government and theology) was really no such thing, just a disguised way of exerting power past a dominant group over subordinate groups. One of its main aims, therefore, is both to prioritise the existential experience of the 'oppressed', and to engage direct with questions of power deployed in different modes of discourse, rather than engaging with questions of pregnant. My get-go experience of this was listening to a paper about eight years ago at SBL, the global Anglophone conference on biblical studies, on 'A Critical Race Theory reading of the Book of Revelation'. The presenter (who was white) outlined the existential experience for black people of seeing the words 'blackness' and 'white' in texts, and then asserted his claim that Revelation was an oppressive text for black people because of its apply of these terms—blackness equally having negative connotations, and white signifying skillful things in general and the presence of the divine in item.

The central problem with this approach is that this not actually what the text says! The discussion 'black' (μέλας) only actually occurs twice, in Rev 6.five describing the third horse, and in Rev 6.12 describing the darkening of the sun. The parallel negative sign of the moon is that it turns 'claret [carmine]', yet no-one suggests that 'red' is a universally negative term. The not bad prostitute in Rev 17.four is described vividly in the colours of blood-red, purple, and gold, and adorned with jewels and pearls. White is mostly a positive term, describing the hair of the risen Jesus in Rev ane.xiv and the raiment of the redeemed repeatedly (Rev iii.5, 3.18, 4.4, 6.eleven, 7.ix and and then on), but it also describes the commencement horse of Rev 6.two, previously thought by some commentators to be a reference to Jesus, but now almost universally agreed to be one of the iv bringers of judgement and disaster, and therefore a negative figure. I asked the person giving the paper, 'Does it matter that your assay is not actually supported by the data of the text?' to which the simple respond was 'no'.

The central problem with this approach is that this not actually what the text says! The discussion 'black' (μέλας) only actually occurs twice, in Rev 6.five describing the third horse, and in Rev 6.12 describing the darkening of the sun. The parallel negative sign of the moon is that it turns 'claret [carmine]', yet no-one suggests that 'red' is a universally negative term. The not bad prostitute in Rev 17.four is described vividly in the colours of blood-red, purple, and gold, and adorned with jewels and pearls. White is mostly a positive term, describing the hair of the risen Jesus in Rev ane.xiv and the raiment of the redeemed repeatedly (Rev iii.5, 3.18, 4.4, 6.eleven, 7.ix and and then on), but it also describes the commencement horse of Rev 6.two, previously thought by some commentators to be a reference to Jesus, but now almost universally agreed to be one of the iv bringers of judgement and disaster, and therefore a negative figure. I asked the person giving the paper, 'Does it matter that your assay is not actually supported by the data of the text?' to which the simple respond was 'no'.

The outcome here is where we locate meaning. For this person, it was the existential feel of responding to the term 'black' which mattered. The difficulty is that the terms 'black' and 'white' did not take these racial and ideological overtones in the ancient world, and they clearly play no office in the text of Revelation when it is read in its social, cultural, historical and approved context. It is people from 'every nation, tribe, people and language' who are dressed in white before the throne!

(Other forms of Critical Theory similarly prioritise the ideas, perception and emotions of the reader, over against what the text might 'mean'; for a Queer Theory reading of Revelation, see Stephen Moore'sUntold Tales from the Book of Revelation. For Moore, the God of the apocalypse is like a modern bodybuilder in competition, surrounded past studio mirrors so that he might indulge in a narcissistic orgy of erotic dominance over creation. This interpretation does not deport much relation to the text itself only rather expresses Moore'due south own projection onto the text.)

And then whilst Reddie could rightly claim that his thinking was not derived from Marxism or CRT, his argument appeared to have much in common with them. He repeatedly spoke in binary terms of 'black' and 'white', and stated explicitly that his concern was to prioritise the 'existential experience of black people'. This led to two of import claims about how we see Jesus, and how we understand the nature of the gospel.

The first claim was that 'Jesus was a black man'. By this, Reddie was using the term 'black' to mean 'the subject area of systematic oppression'. He unambiguously and straightforwardly identified Jesus in his crucifixion with all 'black' oppressed, and Roman imperial power (since Jesus was crucified by the Romans non by the Jews) with white supremacy and its exploitation of blackness people. At one level, this merits is doing not much more than than those who 'inculturate' their understanding of Jesus in terms of their own cultural context; Justin Welby exemplified this in a Tweet final summertime:

Jesus was Center Eastern, not white. It'due south important we remember this.

Only the God we worship in Christ is universal, and the hope he offers is good news for us all. Here are some of my favourites images of Christ from around the world.

What are yours? pic.twitter.com/iXEUdJJFGQ

— Archbishop of Canterbury (@JustinWelby) June 27, 2020

The difficulty here—if we do take inculturation seriously—is that information technology really encourages white people to portray Jesus as white; as ane person commented in response to this tweet:

Let's not be carried away by this "Jesus-was-not-White" rhetoric. All people, races and nationalities painted Jesus as per their ain imagination. So did the Anglo-Saxons. Nix odd.

But this motility has 2 effects. First, it ways that claims and counter-claims nigh who Jesus is are located in the clashes between cultures, and the power dynamic between them. The 2d is that it de-historises the Jesus of the gospels, and ends up being implicitly anti-semitic. As Angela Tilby immediately responded: 'Jesus was Jewish'.

Merely this also leads to an ambiguity in language. Who counts every bit 'black'? I am the son of a migrant who belonged to a despised grouping who has been systematically oppressed by white British ability, and needed both to modify her name and disguise her accent in society to prosper in this land immediately later the Second World War. I am half Irish gaelic. Does that make me or my female parent 'black'? I asked the question in the seminar:

If 'whiteness' is not about white people, and 'blackness' is not nearly black people merely about the oppressed, wouldn't this discussion be helped by coining new terms?

Reddie responded past saying that, yes, in that location could be some confusion. If black people were systematically oppressing others, then they would indeed exist 'white'. And yet the primary experience of oppression in our context is of black people existence oppressed past white people, and so this terminology is still legitimate and helpful. Only using the terms 'blackness' and 'white' at ane moment to refer to different ethnic groups, but at another to refer to social power dynamics of oppression is indeed confusing, and it is non surprising that people are now seeing this every bit 'racist anti-racism'.

The identification of the crucified Jesus s 'black' is not new, merely was showtime popularised by the late James H Cone in his bookThe Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011), and Reddie mentioned Cone at several points in his talk. This is a powerful identification, and it is like shooting fish in a barrel to see how important it has become—but I think making this identification in such a strong and uncompromising style leads to a 2d, related problem.

Additional annotation: I was challenged on Twitter by Zachary Guiliano for my comment virtually Cone. He notes that Cone really argued that 'Jesus was blackness' in his earlier work of 1970 on Black Theology, and that Cone in turn notes that it was coined earlier by others. Zachary helpfully shared shots of a couple of pages of the 1970 book, and I share the texts here:

The definition of Jesus as black is crucial for christology if we believe in his connected presence today. Taking our clue from the historical Jesus who is pictured in the New Testament as the Oppressed Ane, what else, except blackness, could adequately tell the states the meaning of his presence today? Any statement about Jesus today that fails to consider blackness every bit the decisive cistron well-nigh this is a denial of the New Attestation message. The life, decease, and resurrection of Jesus reveal that he is the man for others, disclosing to them what is necessary for their liberation from oppression. If this is true, then Jesus Christ must be black and so that blacks tin know that their liberation is his liberation.

The blackness Jesus is likewise an important theological symbol for an assay of Christ'south presence today because we must make decisions about where he is at work in the world. Is his presence synonymous with the work of the oppressed or the oppressors, blacks or whites? Is he to exist found amidst the wretched or amid the rich?

Of class clever white theologians would say that it is non either/or. Rather he is to be institute somewhere in betwixt, a little black and a little white. Such an analysis is not but irrelevant for our times simply likewise irrelevant for the time of the historical Jesus. Jesus was not for and against the poor, for and against the rich. He was for the poor and confronting the rich, for the weak and confronting the stiff. Who tin read the New Testament and neglect to see that Jesus took sides and accustomed freely the possibility of being misunderstood?

At that place are several things to note here. First, that Cone works with the absolute binary of black and white. Second, these categories of race have picayune or no basis in biological science, only clumps together a diversity of issues around culture, land, language and skin colour, and the modern emergence of the term was rooted in classifications from the colonial era in the 18th century. The language of 'race' is, ironically, rather racist! Thirdly, this does non forbid Cone from imposing his ideological construction of race on the New Testament and the picture of Jesus nosotros detect in the gospels. And fourthly, this leads him to a skewed reading of the texts themselves. Jesus was 'for' the poor, but (maybe uncomfortably) he came to the 'marginalised' to call them to repentance, as a doc comes to ministry to the sick, and he was besides 'for' the rich and respectable; indeed, he was not specially poor (in socio-economical terms) himself. It is rather sorry that anyone offering a critique of Cone's reading is chop-chop dismissed as a 'clever white theologian'.

Cone is clearly aware of the need to chronicle the claims of Blackness Theology to the New Testament, merely I don't recall he actually succeeds.

What evidence is there that Jesus' identification with the oppressed is the distinctive historical kernel in the gospels? How practice we know that black theology is non forcing an conflicting contemporary black situation on the biblical sources? These questions are important, and cannot exist waved aside past black theologians. Unless we can clearly articulate an image of Jesus that is consistent with the essence of the biblical bulletin and at the aforementioned time relate it to the struggle for black liberation, black theology loses its reason for being. Information technology is thus incumbent upon the states to demonstrate the relationship betwixt the historical Jesus and the oppressed, showing that the equation of the contemporary Christ with black power arises out of a serious run across with the biblical revelation.

Black theology must show that the Reverend Albert Cleage'southward description of Jesus as the Blackness Messiah is non the product of a mind "distorted" by its ain oppressed status, just is rather the most meaningful christological statement in our time. Any other Argument about Jesus Christ is at best irrelevant and at worst blasphemous.

i. Nativity. The appearance of Jesus as the Oppressed One whose beingness is identified exclusively with the oppressed of the state is symbolically characterized in his nativity. He was born in a stable and cradled in a manger (the equivalent of a beer case in a ghetto aisle), "considering at that place was no room for them in the inn" (Luke 2:7). Although most biblical scholars rightly question the historical validity of the birth narratives in Matthew and Luke, the mythic value of these stories is of import theologically. They undoubtedly reflect the early Christian community'southward historical knowledge of Jesus equally a man who defined the meaning of his beingness as existence one with the poor…

Once again, notice the anathematising of all alternative views. And over again, there is a systematic misreading of the text in order to fit with the narrative. Jesus wasn't born 'in the ghetto' and his birth was not in especially poor circumstances. In context, Cone's ambition is clearly to reclaim Jesus as the messiah for oppressed black people who feel equally though Jesus has been made 'white'; only in doing so he seems to make absolute claims which appropriate Jesus for a item crusade, instead of correcting previous bias past reading the text better—and recognising that none of us 'owns' Jesus for our ain agenda.

On the question of Roman imperial power and Jesus as oppressed, I asked the question:

If Roman occupying powers are to exist identified with white colonial Christianity, how practice we business relationship for the ascension of affirmative comments virtually the Empire in eg Romans 13, and how exercise we read these positive comments aslope more than negative ones?

Reddie's answer was that Paul was just offer a compromise here, encouraging Christian to accommodate themselves to an evil government near which they could practise lilliputian. The question of accommodation is non unimportant, simply both Paul in Romans 13 and Peter in ane Peter ii offering a much stronger theology of the country than this will let. We must, of course, read Romans 13 alongside Rev 13, simply even doing this does not allow united states to interpret the Jesus of the gospels as primarily concerned with the overthrow of an oppressive government. I asked Reddie this question on Twitter, since it was not picked up in the session:

@AnthonyGReddie thanks for your keynote at the CMEAC conference. Contrary to Jewish kickoff-century liberation movements, Jesus appears to decline the thought that it is Rome who is the primary oppressor, but sin. How does that shape Black Theology?

— Dr Ian Paul (@Psephizo) July 27, 2021

But his reply didn't really address my question: he simply replied that

the historical Jesus was as much against Jewish hypocrisy as he was Roman occupation. So Blackness Theology is opposed to unjust systems not people. It'southward not unconditionally pro-Blackness if that is oppressive in practice.

This is still answering the question is quite humanist, material terms: the problem that Jesus came to save us from is non sin and its offence against God merely social and material oppression and our offence against our boyfriend humans. Reddie quoted (as many liberation theologians do) Jesus' 'Nazareth manifesto' when he quotes from Isaiah 61 in Luke 4. Just he completely detached that from its wider context, and likewise the Benedictus in Luke 1, where the hope for the Messiah is nonjust liberation from oppression, but as well the right worship of God.

This approach fails to make sense of the historical fact that there were plenty of Jewish liberation movements in the starting time century (often in disharmonize with ane some other), but Jesus appears to have rejected them all. This is hardly a marginal question in our reading of the gospels: it is issue behind the repeated question to Jesus 'Are yous the ane who was to come, or should nosotros expect another?' (Matt 11.three, Luke vii.19). The simply plausible explanation for this is that Jesus did not do what the Jews hoped for! 1 of the major questions about the early Jesus movement is: why didn't more Jews recognise Jesus as the promised messiah? And a cardinal office of the answer to that is: Jesus did not throw off Roman power and liberate his fellows Jews from social and political oppression—at least, non directly.

There is a serious danger that this historical reality tin lead to a 'spiritualising' of the gospel, and a failure of the church and the followers of Jesus to take seriously the political consequences of the gospel. Merely it cannot be the right respond to push the pendulum back in the opposite direction and claim that political and social liberationis the gospel. Information technology might be an essential event of the gospel, simply to claim that itisthe gospel can but be done past ignoring what the New Attestation repeatedly says.

If the human problem is primarily nigh social relationships, and not near offence against God, then that is going to have serious implications for what we think well-nigh the pregnant of the atonement. Is Jesus' death exemplary, demonstrating his solidarity with the oppressed, or does it actually effect anything? I recollect Reddie would likely reply the former, whilst orthodox Christian theology has majored on the latter. I asked him about this in the Twitter conversation, merely at that signal he stopped replying.

One final affair that was notable in the whole seminar was a complete absenteeism of any mention of Jesus' resurrection. This omission takes us a long way from the proclamation of the good news that nosotros detect, for example, in Acts, where the message appears to be 'Jesus was God'due south anointed Messiah; you have rejected him; but God raised him from the dead and he ascended to God's correct hand; one day he will come as judge; therefore apologize and be saved'.

More broadly, this day conference was billed equally a joint seminar offered by BIAPT and a Church building of England committee. At a purely academic conference, you lot would expect to come up across a wide range of views, some of which might be consonant with a confessional, orthodox Christian position, and others non. Just at a church conference, yous might await to be able to raise the question 'How do these approaches relate to historic Christian understandings of Jesus, the gospel, and atonement?'

Without request such questions, information technology is no wonder that there continues to exist a serious divide between the views expressed at the event, and the outlook of the wider Church.

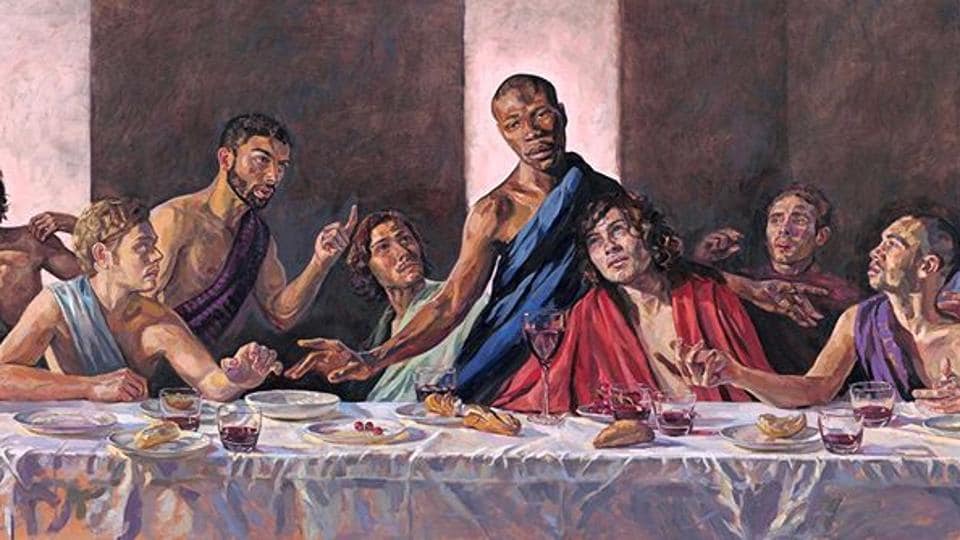

The image above is part of A Final Supper by Lorna May Wadsworth, which casts Jamaican-built-in model Tafari Hinds as the son of God. It was installed in St Alban'southward Cathedral in back up of the Black Lives Matter motility in 2020.

If you enjoyed this, do share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my piece of work is washed on a freelance footing. If you have valued this post, you lot can brand a unmarried or repeat donation through PayPal:

Comments policy: Good comments that engage with the content of the post, and share in respectful fence, tin can add real value. Seek first to understand, then to exist understood. Make the nearly charitable construal of the views of others and seek to learn from their perspectives. Don't view fence as a disharmonize to win; accost the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/life-ministry/was-jesus-black/

0 Response to "Was Jesus black?"

Post a Comment